Intertext

Introduction

Intertextuality is an important concept for describing either direct references to other texts, or more subtle ways of connecting one text to another.

An example of this is the ending of Don DeLillo's novel White Noise. It is set in a supermarket, and the protagonist paints a lively image:

A slowly moving line, satisfying, giving us time to glance at the tabloids in the racks. Everything we need that is not food or love is here in the tabloid racks. The tales of the supernatural and the extraterrestrial. The miracle vitamins, the cures for cancer, the remedies for obesity. The cults of the famous and the dead.

If one has read James Joyce's short story, "The Dead", it is difficult to not see a relationship between the two texts. Where DeLillo mocks the excess of goods and information, and the hopes for an eternal, effortless life, Joyce paints a picture of death and whiteness:

Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, further westwards, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling too upon every part of the lonely churchyard where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

Computational approaches are well-suited to discovering direct quotations but would struggle to find this (at least in 2021). Software developed to disclose plagiarism may also be used to find the use of biblical references in a text, for example, or to find other kinds of similarities. As is so often the case, this may be useful with both single texts and with large collections. Intertextuality that is not based on lengthier quotations may be more difficult to analyse, but it is possible to develop a probabilistic model of influences, as one of our examples shows.

Applications

Elementary

Initially developed for the study of Latin or Greek, Tesserae lets its user search for intertextuality between two sources from the website’s library, for instance between Seneca’s Naturales quaestiones and Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The program then highlights word sequences that are similar in both works and ranks them based on their likeness, giving higher scores to analogue sequences of rare or unusual words in order to circumvent the discovery of common phrases. It is also possible to use Tesserae for English texts, and their library cleverly includes a copy of an English translation of the bible, enabling the user to discover intertextual connections to one of the most quoted and paraphrased texts in Western literature. The English library is, however, both smaller than the Latin library and not fully proof-read, so one should use Tesserae with care.

Advanced

One of the challenges of addressing intertextuality with computational methods is, as Forstall and Scheirer point out (2019, p. 49), “to be clear about the nature of the underlying human phenomenon.” Intertextuality is a broad concept, occurring through many forms: from easily-detectable plagiarism to more elaborated lexical correspondence, often described as paraphrase. Not all intertextuality can be detected through lexical similarity but also meaning in a broader sense, and it can also appear in other than literary forms, e.g. memes. The recent rise of computational tools under many fields within the digital humanities, however, offers great opportunities for the development of quantitative intertextuality studies.

The book Quantitative Intertextuality offers a thorough introduction to the existing tools and methods. The second part of the book also includes examples and resources so that the reader can get a more practical sense of the different methods. The supplementary material of the book has a git repository with which you can run the exercises yourself.

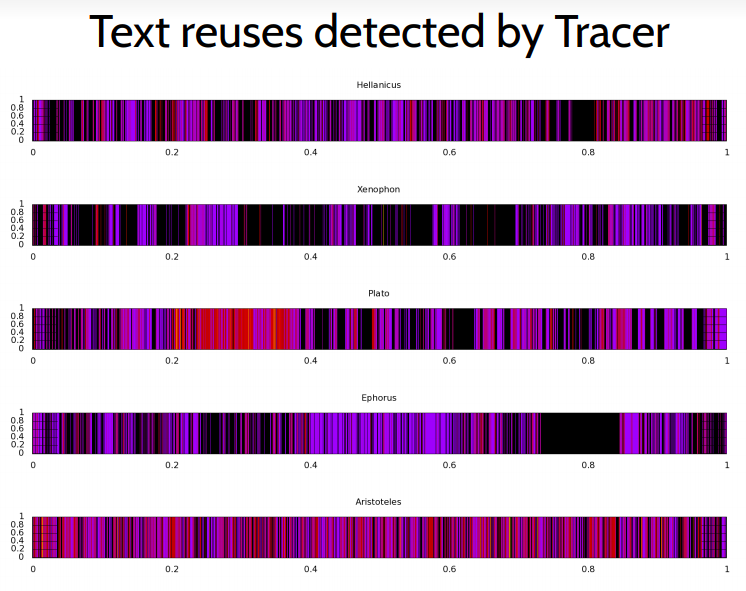

To analyse text reuse, one pioneering tool in the field is TRACER, developed by Marco Büchler as a part of eTRAP, a flexible suite of approximately 700 algorithms aimed at automatically detecting similarities between texts. It can be used in both contemporary and historic contexts. The program is freely available on this webpage. Download TRACER, follow the manual, and investigate two texts that you suspect of text reuse.

Resources

Scripts and sites

-

Supplementary materials and R exercises for the book Quantitative Intertextuality.

- TRACER machine, a powerful and flexible suite of some 700 algorithms for the automatic detection of (historical) text reuse.

- Tesserae, a collaborative project that aims to provide a flexible and robust web interface for exploring intertextual parallels in Ancient Greek, Latin, and English.

Articles

- Coffee, N., Koenig, J. P., Poornima, S., Ossewaarde, R., Forstall, C., & Jacobson, S. (2012). Intertextuality in the digital age. Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-), 383-422. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23324457

- Forstall, C. W., & Scheirer, W. J. (2019). Quantitative Intertextuality. Springer, Cham. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030234133

- Scheirer, W., Forstall, C., & Coffee, N. (2016). The sense of a connection: Automatic tracing of intertextuality by meaning. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 31(1), 204-217. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqu058